The Cult of Busyness: How Rushing Became a Religion and Stillness Became Rebellion

Why Doing More Leaves Us With Less—and How Stillness Can Save Us

For a little more than a week now, I have been ruminating over a voicemail—not because of what was said, but because of what it revealed. The caller, a gentleman who had expressed interest in learning Transcendental Meditation, spoke with the apologetic breathlessness of someone whose life had slipped beneath the undertow of obligation. His tone was weary, the cadence uneven, as though time itself was short-circuiting his thoughts. He was “too busy,” he said, to begin a meditation practice at this time—but hoped to revisit it “once things slow down.”

I sat in silence after the message ended, not with judgment, but with deep recognition. I have heard versions of this same refrain for over a decade: I’m just so busy. As if “busyness” is not only a condition but a credential. A badge of honor. A socially sanctioned justification for delay, avoidance, and—most tragically—a prolonged disconnection from oneself.

There is a name for this condition. It is called The Cult of Busyness.

This cult has no temple, but its worship is ubiquitous. It doesn't need priests—only planners, pings, and perpetual urgency. And unlike traditional faiths that require belief, this one demands exhaustion. Its daily sacrament is the checklist; its ritual, the double-booked calendar. In the Cult of Busyness, stillness is heresy.

Time as Territory

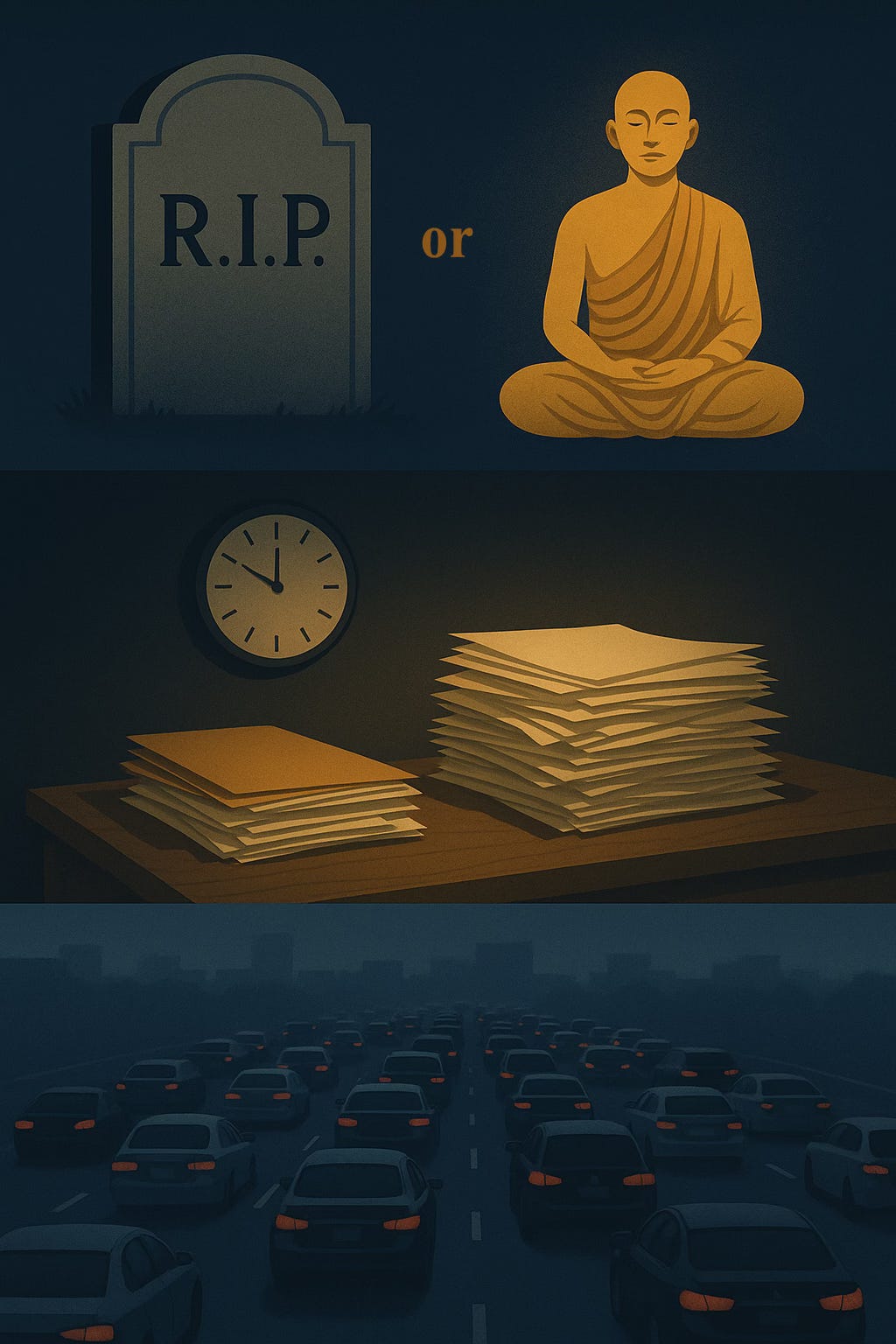

My first real confrontation with this phenomenon occurred not as a meditation teacher, but in a graduate seminar at Georgia State University during what I refer to as my first-leg of Grad School. I was reading Robert Levine’s A Geography of Time, and for the first time, I encountered the idea that time is not simply a measurement—it is a cultural construction. In one of the more salient insights from the book, Levine describes the distinction between clock time—structured, numerical, mechanistic—and event time—fluid, intuitive, relational.

This binary, I realized, was not just theoretical. It was lived. I had lived it. In Atlanta, a city pulsing with deadlines and development, clock time reigned supreme. But when I traveled or later learned to teach Transcendental Meditation after decamping Atlanta to Iowa, I often saw glimpses of event time—particularly among elders, artists, and meditators. I felt it too in my own home when, after dinner, my children and I would relax into a reading as a family, watching a movie, or a snuggle that bore no allegiance to the clock.

Levine’s thesis confirmed something I had long intuited: that cultures (and people) don’t simply keep time—they inhabit it. And just as one can be shaped by language or geography, we are shaped by the temporal structures we embrace or endure. The faster the tempo, the greater the cost.

The Physics of Overcommitment

The quote, “Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished,” often attributed to Lao Tzu, highlights the inherent unhurriedness of Nature alongside its perfect functioning. We note a similar idea coming from Maharishi Mahesh Yogi with his quote “Do less and accomplish more.” Both statements reveal a cosmic intelligence embedded in the natural world—a principle of elegant sufficiency, where effort and outcome are aligned not by struggle but by coherence.

Yet in modern life, the opposite belief prevails: that value is determined by velocity, and that the only way to get ahead is to get busy. We cram appointments into hours not designed to hold them, download productivity apps like spiritual talismans, and refer to rest as “unproductive time”—as if the nervous system were an employee to be optimized.

But this isn’t just a philosophical problem; it’s a neurological one. The overactivated sympathetic nervous system—our fight-or-flight machinery—cannot distinguish between running from a lion and running late to a meeting. Both trigger cortisol. Both shrink the prefrontal cortex’s executive functioning. And both keep us locked out of the restorative states associated with intuition, insight, and inner peace.

We do more, but understand less. We move faster, but arrive nowhere. The Cult of Busyness, for all its noise, leaves us hollow.

Stillness as Resistance

Teaching Transcendental Meditation for over a decade now, I have sat with people from nearly every walk of life—corporate executives, students, artists, new mothers, trauma survivors, retirees. Some seek calm, others clarity. But nearly all come with some version of the same quiet confession: I am tired of always being on.

Stillness, in this context, is not a luxury—it is liberation. To sit in meditation is to opt out of the cult. It is to reclaim the nervous system from the tyranny of adrenaline and invite it back into rhythmic alignment with life’s deeper pulse. It is to remember, even for twenty minutes twice daily, that being is not dependent on doing.

And yet, it is precisely this stillness that so many resist. The man from the voicemail, kind and sincere as he was, could not yet give himself permission to be still. Like so many, he had been conditioned to believe that to pause is to fall behind. That busyness is virtue and that rest must be earned.

But what if rest is not a reward—but a right? What if stillness is not indulgence—but intelligence?

The Inherited Myth

Part of the reason this cult persists is because it masquerades as moral. Busy people are seen as dedicated, hardworking, valuable. Unbusy people are seen as lazy, unfocused, even selfish. But this is a fiction born of capitalism, not consciousness.

In my 2004 Amazon review of A Geography of Time, I noted that Levine does not assign blame to any one cultural orientation—but does point out that societies organized around industrial efficiency tend to prioritize speed over humanity. This has consequences not just for health and happiness, but for charity and compassion. Fast cities, Levine’s research shows, are often less kind.

Think about that: when we rush, we overlook. We cut off not just traffic, but empathy. We make less eye contact. We help less. We see less. The Cult of Busyness doesn’t just rob individuals of their peace—it corrodes our social fabric.

An Invitation to Exit

There is another way. Not one of resignation, but of redesign. It begins with a simple but radical act: redefining success.

What if success looked like aligned effort, not frantic action? What if accomplishment meant not what you ticked off the list, but how present you were while doing it? What if rest was not a pause between tasks, but a sacred rhythm of the whole?

Transcendental Meditation, as I have seen it unfold in the lives of those with whom my wife and I have worked over the years, doesn’t just reduce stress—it restores rhythm. It allows the practitioner to inhabit middle time—neither tethered to the ticking of the clock nor drifting aimlessly through events, but attuned to something subtler: the inner tempo of Self.

We need not flee to a monastery or unplug from modernity. We need only pause. Even briefly. And in that pause, we begin to remember who we are beyond the roles, beyond the to-do lists. We remember, as Maharishi taught, that “life is bliss.” Not a reward for the efficient, but a birthright for the aware.

A Final Reflection

To the man who left that voicemail: I hope you return. Not because I need another student—but because you deserve another moment. One that is yours alone. A moment without apology. Without rush. Without the heavy robes of productivity wrapped around your spirit.

To all of us caught in the cult, this is not a condemnation, but a reminder. We are not machines. We are not brands. We are not tasks to be completed. We are sacred rhythms waiting to be remembered.

And perhaps, in choosing stillness, we will discover that the very peace we seek is not ahead of us—but within.

So, learn to be still. You may just find busyness is wholly unnecessary.

To learn more about Transcendental Meditation, visit: https://www.tm.org.

—

Dr. Baruti KMT-Sisouvong, along with his wife, Mina, serves as Director of the Transcendental Meditation Program in Cambridge and the larger area of Metropolitan Boston. They are parents to four beautiful children. To learn more about him, visit his website: https://www.barutikmtsisouvong.com/.