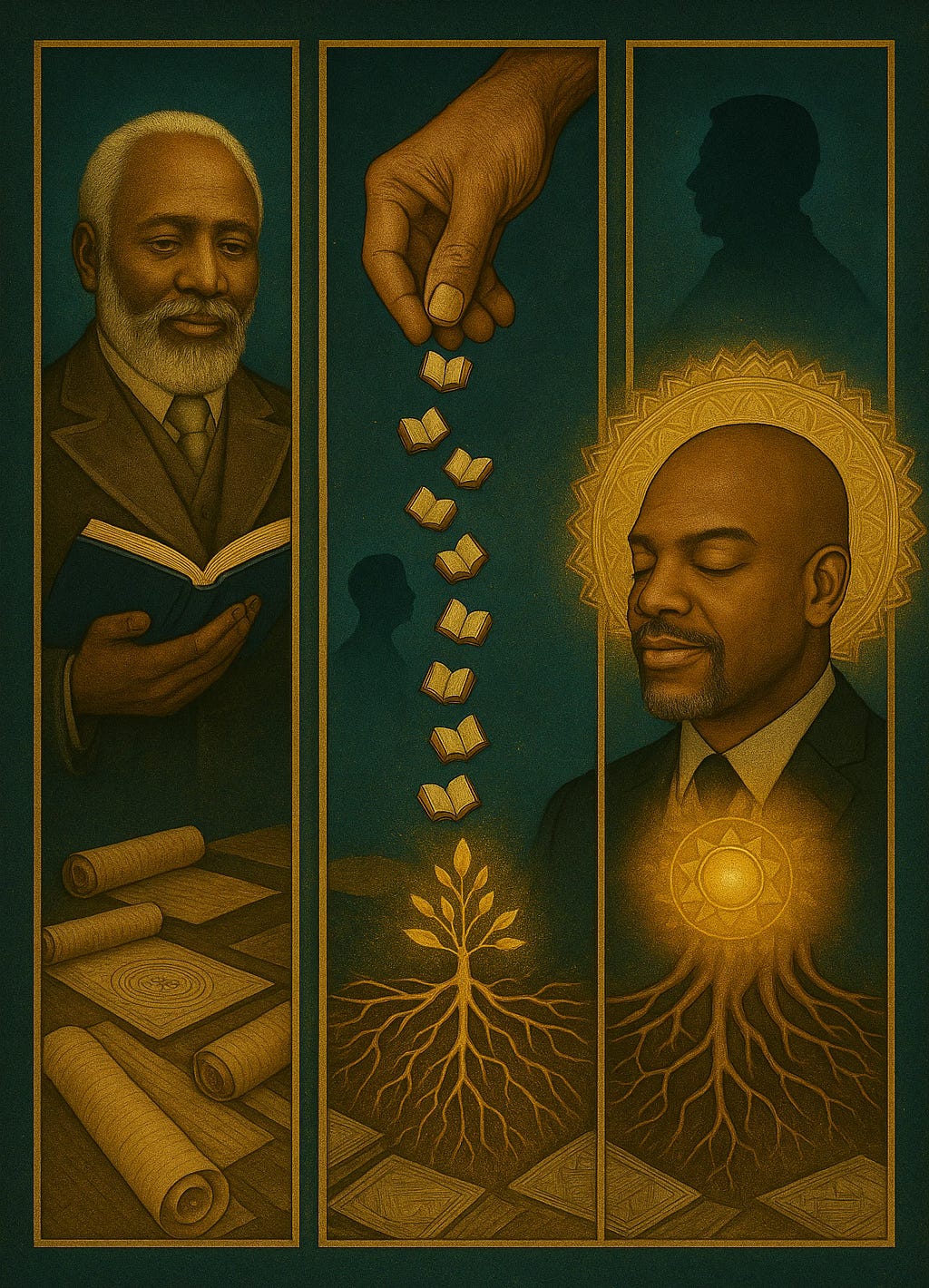

The Seeds Were There: Firmin, Hilliard, and the Early Spiritual Roots of My Framework

Firmin wasn't just writing in defense. He was writing in alignment.

In 2005, while taking classes during my first leg of Grad School in Atlanta, I was handed a book that would, in hindsight, mark one of the earliest stirrings of a framework that would not fully reveal itself to me for nearly two decades.

Dr. Asa G. Hilliard III (aka Nana Baffour Amankwatia II and, reverentially, as Baba.)—my then mentor and now elder in his ancestral home—walked into class that evening with a glint in his eye and a book in his hand. He greeted me with the kind of broad smile that meant something important was about to unfold and said, “Man! Have I got a book for you!”

The book was The Equality of the Human Races: A Positivist Anthropology, initially published in 1885 in French and available for the first time in English in 2000. The author, Joseph Anténor Firmin, was a Haitian scholar, diplomat to France, and fierce critic of the use of “scientific racism” of his time. Firmin’s work was written as a direct and devastating rebuttal to Arthur de Gobineau’s Inequality of the Human Races—a text that had gained prominence in 19th-century European academic circles as justification for racial hierarchy and African inferiority.

Dr. Hilliard handed me Firmin not as a historical footnote, but as a call to arms.

I remember thumbing through the pages before class began, again during the break, and afterward with increasing urgency. The argument was compelling, but what struck me even more deeply was Firmin’s method: his calm, precise use of reason; his layered analysis of race as a social construct; and his refusal to abandon the spiritual dignity of African-descended people even while engaging in scientific discourse. It was the kind of scholarship that rang like a tuning fork deep in my spirit.

After class and our obligatory conversation, I went home and ordered a hardcover copy. Within days, Dr. Hilliard suggested I develop a talk on the book for the upcoming Association for the Study of Classical African Civilizations (ASCAC) conference. With his encouragement and guidance, I was invited to deliver remarks during the Opening Plenary Session as part of a panel that included Dr. Kobi Kazembe Kambon, Dr. Layli Maparyan (currently serving as President of the University of Liberia in Monrovia), and Dr. Hilliard himself—an experience that would prove transformative.

Then, after launching my radio show in 2007, I had the rare pleasure—on 16 December of that year—of interviewing the very scholar responsible for Firmin’s work being translated into English for the first time: Dr. Carolyn Fleuhr-Lobban. Our conversation aired on my show Connecting the Dots, a broadcast I created to explore overlooked ideas and voices at the intersection of scholarship, culture, and spirit. It remains one of those contemplative moments when the hand of Nature feels unmistakable. It reminded me of the many ways a good idea—particularly one long overlooked—echoes through time until it finds the minds ready to carry it forward. Firmin’s work had waited over a century. And then, through her effort, it spoke again.

In March of 2008, I had the opportunity to deepen this unfolding even further by sitting on a panel at the National Council of Black Studies (NCBS) conference in Atlanta, Georgia. The panel, titled "Let the Circle Be Unbroken: An Exploration of Anténor Firmin and the Spiritual Component of Human Solidarity," offered space to reflect not only on Firmin’s philosophical genius but also on the sacred imperative behind his work—a call toward unity that transcends time.

Positivism and Power: Firmin’s Method as Medicine

In my talk and in the brief Amazon review I later wrote, I reflected on three central threads in Firmin’s work: his dismantling of race as a biological reality, his analysis of the Black identity of ancient Kemetic peoples, and his sweeping documentation of African contributions to global civilization. Now remember, this was done in 1885.

At the time, I understood Firmin’s approach as radical—particularly given his use of Positivist philosophy to challenge Positivism's own weaponization. He met the “science” of white supremacy with superior science, not to mimic the worldview of his opponents, but to unmask its fundamental incoherence. In chapters like “Artificial Ranking of the Human Races” and “Comparison Based on Physical Constitution,” Firmin exposed the faulty logics and bad faith at the heart of European anthropology.

But now, years later, I see that what most moved me wasn’t just Firmin’s content—it was his conscious orientation. He wasn’t just writing in defense. He was writing in alignment. Firmin’s work was structured, thorough, spiritual, and ethical. In hindsight, I now recognize it as a historical example of what I would later come to call a Layered Expression of Non-Local Influence.

He was aware of what was being constructed and deconstructed at multiple levels—scientific, cultural, historical, and spiritual. And he chose to enter the arena fully awake. The same may be said of Baba in how he would dismantle specious arguments and tactics by some scholars who sought to pathologize people of African ancestry. It was powerful to witness first-hand.

Dr. Hilliard and the Transmission of Consciousness

Dr. Hilliard didn’t just teach Psychology and History. He transmitted continuity. Through him, I had the honour of studying in Ancient Egypt with him as we walked the temple complexes and discussed many themes and elements of this Ancient African Society. As a result of this and many other experiences from our initial meeting in 1995 to his transition in 2007, I understood that engaging with works like Firmin’s wasn’t simply academic—it was an act of reclamation and repair. Baba had a way of folding you into a lineage of thinkers and builders, of letting you know that the work wasn’t finished and that your voice—if cultivated—would be necessary.

He saw in me, I suspect, the beginnings of a framework. He didn’t name it. He didn’t try to shape it. He simply handed me a book and said, “Here. Read this. Then speak.”

I did speak. And I wrote. My Amazon review, brief though it was, mirrored the clarity I felt: that Firmin had written something so enduring, so layered, that it required careful digestion. Even then, I sensed that his rebuttal to racial pseudoscience had not only intellectual merit but transformational power.

The Seven Layers Were Germinating

With the clarity of retrospection, I now see that the Seven Layers of Manifestation—my framework for understanding the unfolding of consciousness and culture—were quietly germinating within me in 2005.

Firmin's work addressed the Human-Derived World by dismantling faulty scientific constructions. He directly challenged dominant Constructs of Reality by redefining race, refocusing history, and reframing origin. His citations of African contributions to mathematics, philosophy, and civilization anticipated the need to recover awareness of Universal and Natural Laws. Even his spiritual integrity in the face of opposition speaks to the power of Non-Local Influence—of aligning with deeper truth regardless of who hears you in the moment.

In Firmin, I saw the beginning of an intellectual architecture that could hold both empirical rigor and moral imagination. And in Dr. Hilliard, I saw how that architecture could be lived.

Ancestral Threads and Future Responsibility

So much of what I now teach, write, and speak about—whether through my Substack essays, books, meditative frameworks, or public talks—can be traced back to that moment in class and other such epiphinal moments. A book passed hand to hand. A mentor’s suggestion. A podium and a room full of elders and peers. A review written late at night with fire still stirring in the chest.

If I hadn’t said yes to Baba’s suggestion, and other such moments along the way, I don’t know if the Seven Layers would have ever arrived as they have. But because I did—because I followed the thread—I am now able to offer something whole and rooted. Not new for novelty’s sake. But new in the way that gardens are always new: emergent from old seeds.

Firmin’s work is once again rising in scholarly circles. His name, once omitted from mainstream histories of anthropology, is now beginning to find its rightful place. But even if the world had never caught up, his alignment with truth would have ensured that the vibration of his work would echo forward.

We must write like that. Speak like that. Teach like that.

Not for applause. But because the future will find us, and it deserves to discover in our work something coherent, beautiful, and whole.

Closing Invocation

I end with gratitude—to Joseph Anténor Firmin for his clarity, to Dr. Asa Grant Hilliard, III (“Baba”) for his vision, and to that younger version of myself who said yes to the moment.

The seeds were there.

Now the garden has begun to bloom.

And now, I pass to you what was handed to me—knowledge for acting upon.

—

Dr. Baruti KMT-Sisouvong, along with his wife, Mina, serves as Director of the Transcendental Meditation Program in Cambridge and the larger area of Metropolitan Boston. They are parents to four beautiful children. To learn more about him, visit his website: https://www.barutikmtsisouvong.com/.